Winning a bid is not guaranteed no matter how many best practices we follow but the odds of winning increase when we do.

A stellar proposal can lose and a mediocre proposal can win. Why? Because humans are not machines. A successful bid is based on more than our solution.

Evaluators, reviewers, and decision makers are biased and take shortcuts—just like you and me. Our decisions go through an emotional filter that is sometimes referred to as the “automatic brain.” This part of our brain processes information faster than our “manual” (conscious, intellectual, analytical) thoughts. Decades of research validate that our automatic brain is efficient (burns fewer calories), is active at all times, and is almost always correct. This is why we have come to rely on it so much. Our automatic brain is continuously learning. That learning turns into memories, which leads to expectations based on these memories.

Expectations form biases and preconceptions. We see it in sales and marketing all the time. For example, if a decision maker has had bad experiences with our company, then they may expect a disappointing performance again. In this case, a proposal that should win because it meets and/or exceeds the criteria will most likely lose.

Biases and preconceptions help form our industry’s best practices. These are factors that we can apply to help evaluators conclude—with their automatic (and manual) brain—that we are trustworthy, capable, and better than our competitors. Case in point: evaluators may learn that the quality of the proposal is indicative of the quality of the solution. Is this true? Based on their experience, yes. Conversely, if polished proposals were associated with poor performance, then they would be biased against elegant bids.

Another example might be our customer has learned, through trial and error, that measuring process execution results in better outcomes. When they tracked asset performance, they were able to rapidly progress compared with an ad hoc, unmeasured approach. For this reason, specific numbers in bids—things that are quantitatively verified—builds more trust than explaining performance without proof or using generalities.

Many of the shortcuts your brain takes to determine if something is better are going to be similar for evaluators. For example, a poorly written document riddled with grammatical errors and misspellings negatively impacts how you perceive the professionalism of a related product, service, and solution provider. The same is true for the vast majority of reviewers.

At its core, decision makers want to know two things:

- What is your solution?

- Why should I pick you?

We want our best practices to efficiently help answer those two questions. To do so requires using more than one gold standard. Our proposals benefit when we use a symphony of smart standards to say why we are the right choice for this project. Best practices are demonstrative evidence of our professionalism, quality, efficiency, efficacy, and more.

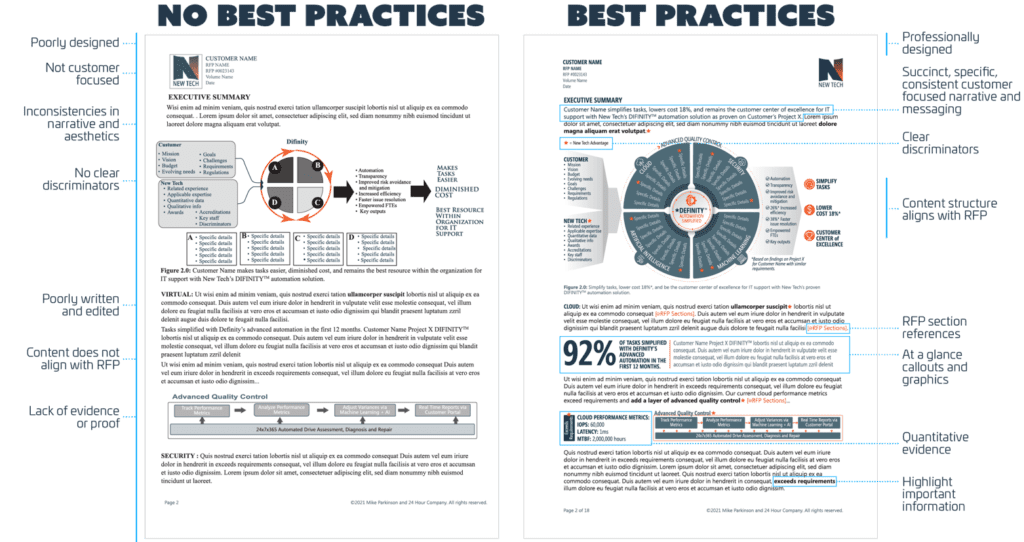

Rather than take my word for it, let’s look at two bid pages in the graphic. One ignores best practices. The other blends different techniques to help reviewers make the right selection. Which page looks more professional and shows a greater investment in this effort – left or right? This process is exactly what your prospects are automatically doing for each bid you submit. They can’t turn it off.

Prove you are the top choice. Use several best practices to quickly and clearly explain your solution and why you should be chosen—automatically.

This article was written by Mike Parkinson.

Mike Parkinson is a geek. He is CPP APMP Fellow, 1 of 36 Microsoft PowerPoint MVPs in the world, best-selling author, and an industry thought leader. Mike’s keynotes, training and books (“Billion Dollar Graphics” and “A Trainer’s Guide to PowerPoint: Best Practices for Master Presenters”) help companies succeed while saving money and time. He is a partner at 24 Hour Company, a premier creative services firm, and owns Billion Dollar Graphics.